It was the first of July, 4am, at Tan Son Nhat International Airport in Saigon. Visa in hand, I take a Grab Taxi to the hostel my friends were staying. I get however many hours of sleep I can muster. The excitement of a new country, a new place is like none other.

Two days were spent in the city, then we got our motorbikes. My friends had rented them for 10 days. I signed on for two months.

I rode on a Honda Blade 110cc motorbike from Saigon north to the border of China. I drove over 4000 kilometers of highway, rural routes and even dirt tracks, at times in the rain. This is a briefing of what I saw and experienced, in what has been, thus far, the adventure of my lifetime.

The Route

The route followed coastlines, circling up the to hills, and then back to the coasts once more, the goal being the mythical North. Motorcyclists taking the North-South route told me of the stunning sights they had seen, particularly in the most-northern province of Ha Giang. What I experienced, what I saw, may briefly intersect with other Vietnam “backpacker” guides, but oftentimes it will not.

There are 3 major classes of road in Vietnam: CT, QL, and DT roads. CT roads are expressways — motorbikes are not permitted on them. QL roads are major highways. QL1A is a major truck route that hugs the coastline, one of the more annoying roads to drive on. DT roads are rural routes with some sections being less maintained than others. I’d say you get asphalt about 75% of the time on a DT road.

The Start

Max, Ben, and I rode together for the first 10 days of the trip. During this time we had a taste of the coast line at Vung Tau, our first destination leaving the neon-illuminated insanity that is Saigon. While leaving the city, in the pouring rain, we must have lost Maxie at least twice. Leaving either the two major cities in Vietnam has to be the most stressful part of any Vietnam motorbike tour. The motorbike lane is small, frequently blocked by cars, and you negotiate with truckers and bus drivers constantly passing you, giving you the customary short beep.

After a brief stay on the coast and with a recommendation that we see Cat Tien National Park, we make our way into the hills, passing remote villages and rice paddies that matched our preconception of what Vietnam was. I remember vividly, on the stretch of QL20 from Cat Tien to Bao Loc, when we had stopped for a Ca Phe Sua (Coffee with Condensed Milk) at the only place we could find open in the middle of the day. Within 5 minutes of us placing our order, a young woman comes on a motorbike carrying a small bag with 3 coffees. The price we paid was the same as anywhere else, 10,000VND (about fifty cents). Rather then try to explain that they do not sell coffee, they allow us to stay and wait comfortably while they ordered coffees for us. The kindness of the Vietnamese people is one constant that remained true throughout the adventure.

Eventually we ended up in Da Lat, a town known for coffee and a comfortable 27°C temperature throughout the year.

The first time I almost died

After Da Lat we descended to the coastal resort city of Nha Trang, where Russian and Chinese are heard more often than the country’s mother tongue. Twisty, mountainous roads turn into highway as the land flattens near the South China Sea. On the major highway entering Nha Trang, I see Ben in front of me pass a large truck. Being that I’ve been following him for the past 2 hours, I figured it must have been safe to pass as well. I move into the left lane, seeing a car approaching in the opposite direction. I downshift and prepare to pass, thinking quickly that I have enough room and the car will just pull over a bit (yes, I know) and let me by, as traffic rules are never followed in Vietnam anyways. Seeing an impending accident, I shift into second gear, and pass the truck with only, if memory serves, 2 meters of clearance. I take a short deep breath, shocked at what had happened. When we arrived at Nha Trang, I asked Max if he saw it. He replied, “Dude, I thought that was the end.”

When riding a motorcycle, it’s important to have an healthy fear of what can happen, and what does happen, to riders almost every day.

Nha Trang was the last stop for Max and Ben. We said our goodbyes, and I told them I would see them in Germany next March (which I did, and then Covid-19 happened while I was there). I rode on with my new friend Hazel, also a German, to the next city: Qui Nhon.

Qui Nhon

Qui Nhon is not a particularly touristic city. Interestingly enough, this is the one section of Vietnam that is a desert year-round in an otherwise tropical and humid country. I stayed at Life’s a Beach Backpackers, a hostel built right next to a beach, with no celluar signal or wifi to speak of. The most peculiar aspect of every guest was that they couldn’t get themselves to actually leave. A girl from New Jersey said she was going to stay 3 nights originally, but it had turned into 12. I had found a real-life Hotel California.

At breakfast, once you got your eggs at the bar, the staff asked “one more night?”, and the answer was almost always the same around the bar. During the day, guests would lounge around, reading or smoking cigarettes. Perhaps going down to the water and having a swim if the mood struck. Sometimes there was a short class on how to make spring rolls. Time moved at a snail’s pace. Life’s a Beach is actually a ways from town, roughly 20 minutes, so the bar which sold food, water, and of course alcohol was the most convenient option for life’s necessities.

Every night, every guest would go to the bar like clockwork as if it were church. We drank, exchanged travel stories, life advice, and did immature, frankly college shit. I hate to admit it, but my first “beer bong” was in Vietnam, despite having just graduated college two months prior. I met a older man in his 40s who knew one of the bartenders, who hailed from Seattle. He told me how he was some sort of higher-level manager at Microsoft, who had come to Vietnam to visit his friend and try to get his drinking down, despite being about 20 shots in as indicted by the chalkboard where we kept “score.” He told me I chose the right career and wished me luck on my future, advising me that if I stick around it will be “lucrative” for me.

I was locked into Life’s a Beach for four nights instead of one. The last night was Hazel’s Birthday. She was to stay at Life’s a Beach and work in exchange for food, housing, and a motorbike, allowing her to prolong her trip. Hazel had lived in different parts of Asia for several years at this point. An architect by education, she worked for an NGO in Nepal for a time, where she had the same deal she had at Life’s a Beach. It’s yet more proof that there are ways to live a life full of adventure, if you’re creative enough, but honestly, willing enough to find them.

Life doesn’t need to be monotone. We live in a world where English is spoken as the international Lingua Franca, where work can be done online, where some lucky fools even earn their keep through making videos. Such a life is more risky than the prescribed route in western societies, but the risk is waking up one day and realizing how you really could have lived your dreams, if you had only given it a shot. I want my life to be a song of many movements. I want crescendos and decrescendos. Staccatos and trills. I want it to be a song that others will listen to.

Against all odds, the bar does actually close at 2am. Anyone who is left goes down to the beach, strips naked, and swims out to a floating raft to look at the stars. I think it’s about time to switch gears here.

The second time I almost died

Ben and Max made a name for me, “Predicament Michael,” because it seemed like at least once an hour I would be in some minor, yet aggravating situation. I wish I could say that it weren’t true. One instance that comes to mind was at Cat Tien, when the shower went out during a power outage. I was, of course, caught mid-lather.

From Qui Nhon I set forth west into the mountains. I took the DT670, seeing villages, breathtaking vistas, and kind people who wanted only to say hello and practice a bit of English. That night I slept in Kon Tum, deep in the southern Vietnamese highlands.

The next morning I set out onto AH17 — a section of the Duong Ho Chi Minh, aka the Ho Chi Minh Highway. My goal, lofty in retrospect, was to get to Hoi An that very night. In the mountains, a major city or international-standard hospital virtually light-years away, a car passed me on a curve. To avoid the car I instinctively start braking and pulling to the right, right onto a small section of gravel, loosing the control of the motorbike at 40 kilometers an hour. I’m launched forward a several meters, landing on my arms and legs. As fortune had it I was wearing my arm pads, but I had no knee pads. I was mildly cut up on different sections of my body, with a rather nasty gash on my knee. Three locals stopped to help me. Two of them propped my bike back up, and made sure I was alright. I tried to ask for a phone to use google translate, as my phone screen had shattered, but the language barrier was too strong. Two of them left, and one stayed once I brought out my first aid kit. She helped me dress my knee, washing it, sanitizing it, and then wrapping a bandage. I could only say thank you in Vietnamese, and I tried to offer her money because I didn’t know how to properly thank her, but she vehemently refused.

Within 5km I was in another small village. I saw some kids outside of a shop playing, and I motioned to them to get someone to help. They brought out their 16-year-old brother, who had fortuitously spent the last month in Kon Tum studying English. He brings me to the village clinic. This clinic has about 3 beds and is staffed by the lonely doctor, but they have Novacaine, Betadine, and all the other accoutrements of any doctor’s office. He advises me, with the teenage boy playing translator, to see another doctor once I’m in a larger city. The young boy shows me the phone repair shop, and tells me that his mother is calling him to get back home. That day was especially harrowing, and I decided that there was no way to I was going to make it to Hoi An that night. I stop at the village of Kham Duc at around 5 pm, and walk into a homestay I read about. She tells me that she has no more beds for me, but she sees my situation and offers to lay down a mattress in her own living room for me to sleep on. She tells me that she’s seen bikers get injured like I have before, helps me get more bandages the next day. For a few weeks after my spill, bandages and antibiotics ate up a sizeable portion of my budget.

I am eternally grateful for all the help I got from locals along my travels, and I acknowledge just how lucky I was. The accident was jarring, but let’s be real, worse things can happen on a motorcycle.

Hoi An

The next day, taking my time, I head down the mountains to Hoi An. Hoi An is on every travel blog about Vietnam you have ever read. It’s touristy, but it is simply the most charming city in Vietnam. It is known for its excellent tailors. I have 5 shirts made from quality fabrics, which I had to negotiate down from $170 to $130. While it’s not cheap, and very touristy, you cannot go to Hoi An without getting something tailored. I can attest that people notice when you wear clothes that are fitted just for you.

After Hoi An, it was the famous Hai Van Pass, made popular by Top Gear, and then onto Hue. Hue is the ancient capital city of Vietnam, and it is known for the spicy noodle soup known as Bun Bo Hue. From Hue, I made an early start for Khe Sanh, the beginning one of the most breathtaking drives of this excursion.

The Khe Sanh — Phong Nha reach

Khe Sanh has no hostels, no homestays, as it is nowhere near the typical tourist’s route. It is part of the Ho Chi Minh Highway, which lies along the former Ho Chi Minh Trail, a supply route used during the American war. The drive from Khe Sanh to Phong Nha hugs the border of Laos, deep in the mountains, passing through villages where people are living in simple wooden houses. And yet, as it is in everywhere in Vietnam, they are connected to the world through cell phones regardless of how remote they may be.

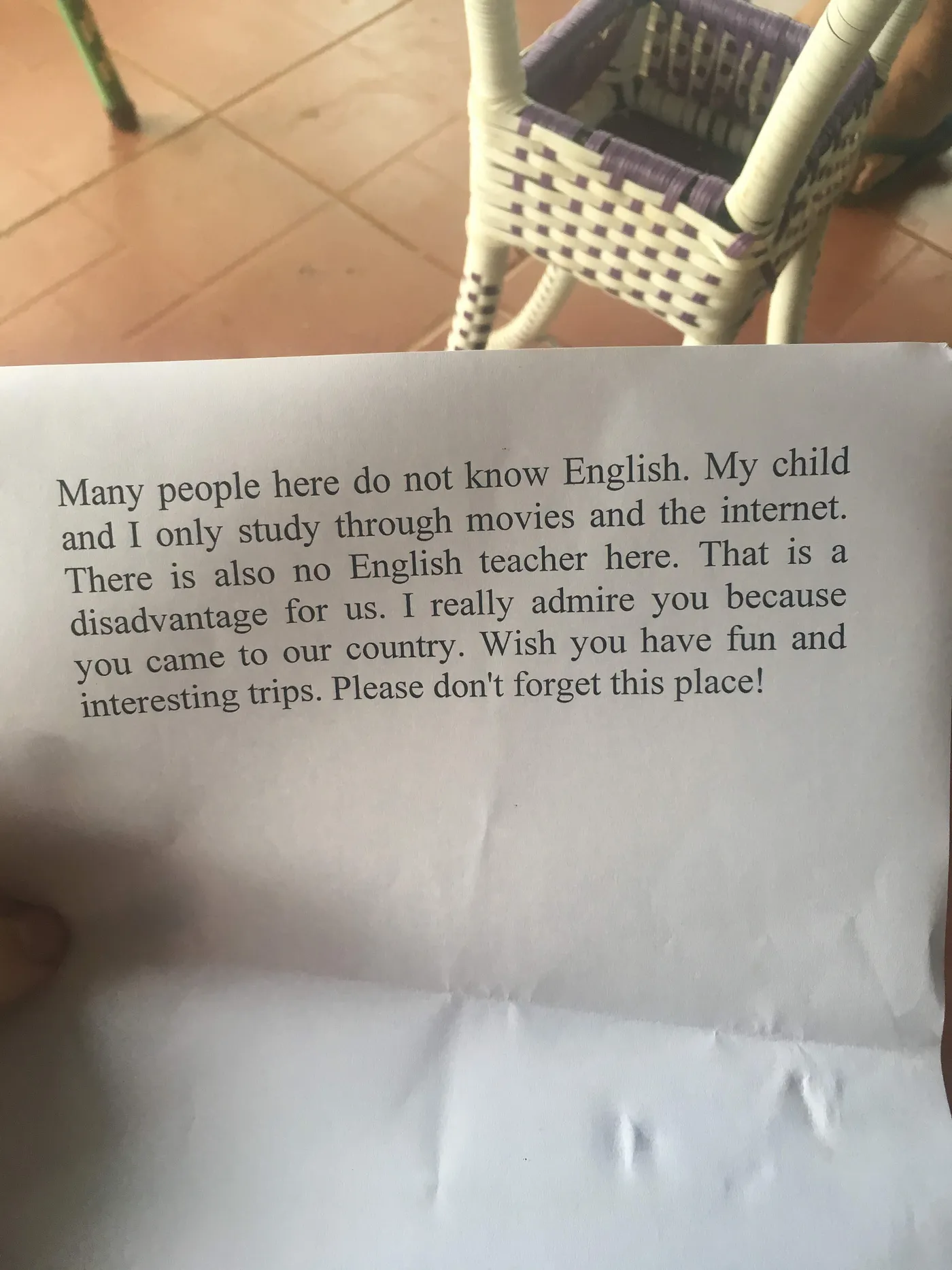

Here, once again, comes the famous Vietnamese kindness and hospitality. I stopped for a coffee at a place called Time Coffee. The man welcomed me and his entire family was excited to see me. They wanted to know who I was, where I came from, where I was going. What struck me at the time, and has remained in my thoughts to this day, is the note he printed out for me and wanted me to have. Throughout my motorbike travels, I had never felt unwelcome by the Vietnamese people. When he gave me the note, he asked me to read it for him, so that he knows what the words sound like.

Years later, my friend went to the same cafe, and received the exact same letter. Great marketing gimmick!

The rest of the drive is nothing but sweeping mountain views, twists and turns through jungles, with not even one car and on a rare occasion a motorbike. The air quality was so amazing that day that there were sections where one could see the South China Sea, nearly 60 kilometers away. The drive that day took about 12 hours, breaks included.

At long last, the great North

From Phong Nha, famous for its caves, I took a night bus with my motorbike (a great option to save time especially if the weather is bad) directly to Hanoi. I spent a few days in Hanoi, enjoying the night markets of the Old Quarter, and who can forget their famous Ca Phe Trung, also known as Egg Coffee. After seeing what had to be seen, it was time to continue my journey. I was to make an arc from Lang Son in the east to Sapa in the west, going back to Hanoi via night train. Surprisingly, with the exception of Saigon, this was the only section of my trip where there was rain. And my god, did it pour. From Lang Son it took 4 days to get to Meo Vac, the beginning of the world-renowned Ha Giang Loop. The pictures I have here don’t do it justice, not even close. It is the most beautiful, breathtaking region I have ever seen. There are even sections where you can cross the Chinese border (perhaps semi-illegally) into Yunnan province. If you are going to Vietnam and you’re okay with the risk of a motorbike, make every effort to go to Ha Giang. I’d even skip Sapa for Ha Giang if I was forced to choose.

Around the Chinese border I popped my tire. Riding to the shop with a flat tire is a very awkward dance where you physically lean forward to put all your weight on the good tire (as most flats happen on the back tire). God forbid you pop your front tire somehow.

The time I was almost stranded

I spent a night in the village of Na Tri, at a lovely homestay called Tho Homestay, where you essentially sleep as rural Vietnamese do, on hard beds in a wooden house that is kept off the ground with wooden beams. The next day I wanted to make the long drive to Sapa, but Maps.Me recommended a route for me that was 15 minutes shorter. That seemed a bit odd as the road it showed me didn’t have a number on it, but maybe it knew something that I didn’t.

This assumption turned out to be extremely wrong. I took the road and it was extremely bumpy, thinking it would improve and become paved after a short while. The road was literally all bumps and rocks, with the occasional stream which I forded on the bike by revving the engine and holding on. I notice a strange sound coming from the bike, so I stop at what appears to be a small restaurant, and a man there adds oil to my chain. The sound stops, and I continue on a few kilometers. Still, something is off about the bike. I smell smoke. I stop at another house, and I tell the man inside my bike has a problem. He opens up the chamber to check the oil, and only smoke comes out. There was no oil in the engine as far as he could tell. I wait an hour for his son to bike to the next town over and buy some oil. While we are waiting, we managed to string together a conversation using google translate. He shows me family photos from Ha Long Bay, and it turns out his name is Tom, which is also my father’s name. His son comes back and he changes my oil for 150,000VND, and I am grateful. I’m on my way. Yet, the same problems arose maybe 500 meters down the road. I check the oil chamber again, and it is still smoking! I call the bike company to ask what to do, and they recommended driving up the road until I see a man with a truck and to ask for a lift back by calling them back and allowing them to translate. This answer did not seem promising, but lo and behold, not one kilometer up the road and I see a truck. The rental company explains the situation over the phone and the man offers to drive me and my bike back later this evening. He invites me to stay at his home, which is another traditional Vietnamese house. Evening comes, and him and his friends attach the bike onto the truck and keep it stable with ropes, and we make the extremely bumpy ride back to Na Tri. I learned that evening that I had gone only 15 kilometers that day, and it took me about 3 hours to do even that. I go back to the homestay, and Tho lets me stay another night, but there is a power outage, so I try to get some sleep without the luxury of a small fan.

The End; it had to come sometime

I took my original route to Sapa, and spent a night there. The next day I took the train to Hanoi. I spent 3 days there, mostly relaxing and spending time with a friend I made back in Lang Son. This marked the end of the best thing that has happened in my life so far. It was these difficulties, the sights, and the people, that made for the trip of a lifetime. In all, I took roughly a month and a half to make this trip, and I barely scratched the surface of what this country has to offer.

What’s next for me

I still have to figure this out. I live in San Francisco now, where I work as a Software Engineer. We’re dealing with the Covid-19 virus, and the governor has issued an order for everyone to stay home. This has given me time to finally reflect on my travels, and save my memories before time will make the details hazy. Being cooped up at home on my computer makes me long for my old life on the road, where the riding is tough, the days long, but the thirst for adventure is finally satisfied.